This paper will highlight the narratives of violence constructed in Peru’s mass media and forms of cultural production, such as literature and film. This myth, however, was based on representations of violence which created indigenous communities in the interior and the Peruvian Left as an internal enemy, perpetrators of terrorism and obstacles to Peru’s economic modernisation. By reinforcing this foundational myth, he retained popular support and legitimised his rule despite a brutal price stabilisation plan and his 1992 autogolpe. In Peru, in particular, President Fujimori presented himself as the saviour of the nation, the sole pacifier of Sendero Luminoso and the captor of their leader Abimael Guzmán. The roots of this shift, however, lay in previous authoritarian regimes which derived their legitimacy, and excluded political opposition, by exploiting deep fears of communism, leftist economic reform and the racial Other. When Chile, Argentina and Peru had all undergone a transition to democracy and neoliberal economic policies following the Washington Consensus in the mid-1990s, it was taken by some as a sign that Latin America was experiencing a shift towards the Western liberal democracy model of development. In the last three decades of the 20th Century, several Latin American countries experienced political violence, authoritarian rule and a reversal of previous Import Substitution Industrialisation and nationalist economic policies. Roncagliolo writes in a self-reflexive mode that is essentially satirical, reflecting and reflecting on trauma discourse and the ways a novel contributes to and changes it. Cueto writes in a sincere mode, attempting to reflect as it were “purely” the processes of traumatization his characters experience. What separates Cueto and Roncagliolo, defining two equally viable and interesting options for portraying post-Sendero trauma, is their degree of reflexivity, the degree to which such “trauma discourse” figures into their formulation.

My argument assumes that any novel aspiring to participate in processes of national reconciliation necessarily avails itself of reified, even petrified, notions of how trauma functions. They present exemplary cases of two disparate approaches to trauma, one satirical, the other non-satirical. Even so, important differences separate them. Both align ideologically with the project of healing that drove the CVR both share with it a common lexicon of concepts related to trauma.

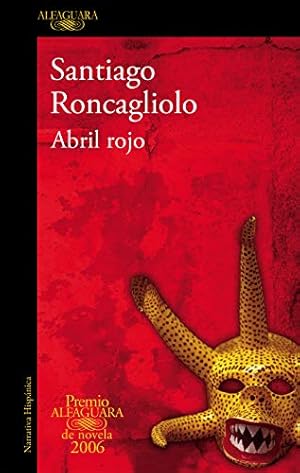

Alonso Cueto's _La hora azul_ and Santiago Roncagliolo's _Abril rojo_, both popular and critical successes, in many ways exemplify post-Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación literary treatments of Peru's armed conflict.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)